The Fields Gone Under: How the September 2025 Northern India Floods—Especially in Punjab—Tore Through Harvests, Supply Chains and Lives

In late August 2025, a series of intense low-pressure systems and unseasonal downpours battered northern India. Rivers that normally fall during the end of the monsoon swelled and overflowed; sudden, heavy rain overwhelmed drainage networks and rural embankments across Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir and parts of Delhi. The result was not a single, slowly developing crisis but a barrage of flash floods and inundation that left many villages under water almost overnight. National and international outlets reported large-scale displacement and dozens of deaths in a few days, with rescue operations rushed in from the army, NDRF and local disaster response teams. AP Newswww.ndtv.com Punjab, situated on the flat alluvial plains of the Indus-Ganges basin, is extremely productive but hydrologically exposed: heavy rains, coupled with breached embankments and saturated soils, turned standing crops—paddy, basmati, vegetables—into soggy losses. The state’s agric

Table of Content

- The event: an extraordinary monsoon, a fast-moving disaster

- On-the-ground devastation: fields, homes, livestock

- Who is helping — and where the official response has been judged weak

- Celebrity and diaspora relief: high-profile adoption of villages

- The agricultural arithmetic: why lost acres translate into supply risk

- Inflation and food security: short-term shock, medium-term uncertainty

- How long until recovery? Why "weeks" may become "seasons"

- Infrastructure and logistics: how floods amplify supply-chain friction

- The human toll: lost income, displacement and food access

- Government finance and compensation: debate over adequacy

- The role of insurance and risk transfer—where the gaps are

- Community resilience: Sikh institutions, diaspora aid and volunteer networks

- Celebrity action: adoption of villages and public attention

- What should be done now? Immediate and medium-term policy priorities

- How long will recovery cost and take?

- What it means for the common person: food, prices and livelihoods

- The narratives that matter: blame, solidarity and lessons

- Closing: urgency, empathy and a path forward

When the monsoon came with a fury few had seen in decades, it did not merely soak fields and roads. It rearranged livelihoods. Across northern India in late August and early September 2025, relentless rain and swollen rivers flooded towns and villages, ripped out homes, and drowned acres of standing crop just weeks before harvest. In Punjab—India's granary—the scale of damage is staggering: officials today put the submerged farmland at roughly 4 lakh (400,000+) acres, with thousands of farming families staring at the very real prospect of losing this year’s entire paddy and vegetable yields. The human cost—lost income, ruined houses, threatened food supplies—will ripple through the economy for many months, if not years.

Let us see what happened on the ground, how huge crop losses translate into shortages and price-pressure for ordinary consumers, the fragile state of infrastructure and logistics exposed by the floods, and how an overwhelmingly community-led relief effort—particularly by local volunteers and Sikh organizations and diaspora—has become the immediate lifeline for the worst-hit people. It also looks ahead: how long recovery may take, what it will cost, and why rushed or inadequate aid could make a short-term humanitarian emergency evolve into a longer-term food-security and inflation problem.

The event: an extraordinary monsoon, a fast-moving disaster

In late August 2025, a series of intense low-pressure systems and unseasonal downpours battered northern India. Rivers that normally fall during the end of the monsoon swelled and overflowed; sudden, heavy rain overwhelmed drainage networks and rural embankments across Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir and parts of Delhi. The result was not a single, slowly developing crisis but a barrage of flash floods and inundation that left many villages under water almost overnight. National and international outlets reported large-scale displacement and dozens of deaths in a few days, with rescue operations rushed in from the army, NDRF and local disaster response teams.

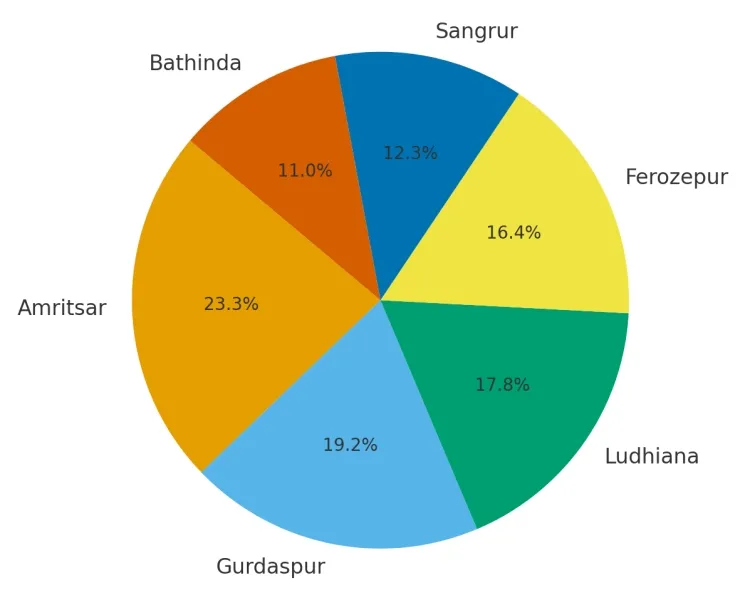

Punjab, situated on the flat alluvial plains of the Indus-Ganges basin, is extremely productive but hydrologically exposed: heavy rains, coupled with breached embankments and saturated soils, turned standing crops—paddy, basmati, vegetables—into soggy losses. The state’s agriculture minister and other officials surveyed fields and reported over 4 lakh acres submerged, much of it paddy close to harvesting time. Political leaders have appealed for immediate compensation and relief, describing current central compensation norms as inadequate for the scale of loss.

On-the-ground devastation: fields, homes, livestock

Walking through the flooded belt is like moving through two worlds at once: the waterlogged calm of fields that would have been golden with grain, and the human chaos where families have had to climb to rooftops, abandon cattle and wait in temporary shelters for food and water. Agricultural experts and district officers have described whole villages where paddy stands bent and submerged, vegetable plots ruined, and seedbeds washed away.

In the border and northwestern districts—names that now recur in rescue and relief reports—vast tracts of basmati and paddy were inundated. In some blocks, the basmati crop, particularly vulnerable and higher-value, suffered near-total destruction in pockets, threatening incomes for entire local economies built around aromatic rice. Livestock losses and ruined fodder stocks add a second wave of damage: even when fields eventually dry, displaced cattle and damaged dairy infrastructure can delay milk recovery and add costs to rural households.

The immediate humanitarian needs were plain: fresh drinking water, safe food rations, dry shelter, healthcare and basic veterinary support. The inability of municipal drains and rural embankments to cope with sudden inflows of rain meant relief convoys and volunteers became the first line of defense, sometimes even before formal emergency services could reach isolated pockets.

Who is helping — and where the official response has been judged weak

Within days, stories emerged of heroic local volunteers, community organisations and Sikh charitable networks mobilising boats, food, fodder and medical aid. Gurudwaras and Sikh NGOs—rooted in decades of local relief networks—activated long-standing channels and volunteers. Sikh communities in other Indian states and abroad also rushed to collect funds, pack ration boxes and charter transport. The result was an immediate, community-driven distribution of essentials to many villages. Media coverage noted that organizations such as Khalsa Aid and other local trusts were active on the ground delivering food, water and shelter.

At the same time, a chorus of political and civic voices criticised the pace and adequacy of formal government relief. Punjab’s Ministers and opposition leaders called on the Centre for a larger compensation package and pointed to the insufficiency of the standard per-acre crop compensation norms—currently framed at amounts many farmers say barely cover even immediate re-sowing costs. The state’s leaders requested release of pending funds from central rural development pools and asked for special relief packages given the scale of damage. For many rural households in flooded districts, official monetary support has been described as insufficient or delayed at the time of reporting, deepening the community dependency on volunteer relief.

This criticism is not the same as saying there has been no government action: rescue missions, evacuations and some official relief camps were in place and national agencies had been mobilised. But as several local leaders and analysts put it, the scale and immediacy of relief needs—especially for farmers who must replant, repair bunds, or replace seed and fertiliser—mean that delayed compensation or inadequate per-acre help will leave many households exposed for weeks. That gap is precisely where community networks have played an enormous role.

Celebrity and diaspora relief: high-profile adoption of villages

Amid those community efforts, several Punjabi artists used their platforms and resources to provide direct help. Singer-actor Diljit Dosanjh announced the adoption of 10 villages in flood-hit districts, mobilising teams to deliver food packets, medicine and clean water and pledging longer-term rehabilitation support through partnerships with local NGOs. Ammy Virk (often spelled Ammy/Amarinder Virk in coverage) announced adoption/support for 200 homes, promising rebuild assistance and temporary shelter. Several other regional celebs—actors and singers with strong Punjab ties—publicised relief initiatives and in some cases helped fund ambulance vans or mobile medical teams. These high-profile interventions both brought immediate resources and drew national attention to the humanitarian need.

Celebrities alone can’t replace a system of compensation, crop insurance and disaster preparedness; but their swift actions delivered food, shelter and morale boosts to many communities—especially where bureaucratic channels were slow to pay out or complicated to access.

The agricultural arithmetic: why lost acres translate into supply risk

A headline number—4 lakh acres submerged—is stark, but understanding how that translates to food availability, market prices and real household pain requires unravelling the agricultural math.

Punjab is a major paddy-growing state. A single acre of paddy, at local yields and depending on variety, can produce several hundred kilograms of rice; aggregated across hundreds of thousands of acres, the crop loss is substantial. The timing matters even more: the crops flooded in many areas were at a late stage ahead of harvest. Late-stage inundation typically destroys yield, and even if some grain can be salvaged, quality deteriorates and much produce is unfit for procurement by formal agencies like the Food Corporation of India (FCI). Officials and experts have flagged two worrying dynamics:

-

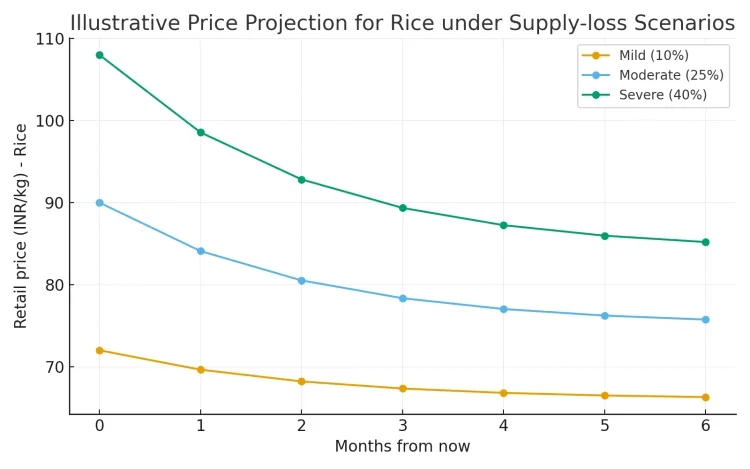

Immediate local shortages of freshly harvested rice and certain vegetables. Where standing crops perish, local markets—which normally rely on steady harvest flows—see a sudden reduction in supply. That can push up wholesale and retail prices in nearby towns within days.

-

Pressure on the public distribution system (PDS) and procurement. Punjab is a key supplier for central rice procurement. If flood damage significantly curtails procurementable rice, there may be pressure to source rice from other states or to dip into buffer stocks—actions that can have fiscal and distributional consequences, and that may appear in prices over weeks. Analysts already warned that paddy price expectations could shift appreciably in local mandis: what had been expected to open at a certain wholesale price could jump because farmers and traders will attempt to salvage value from reduced supply.

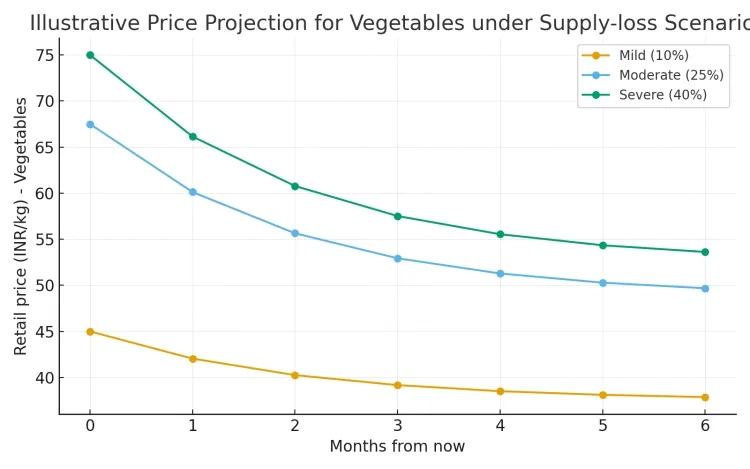

Beyond rice, vegetables and other perishable crops are especially vulnerable: standing vegetable fields immersed for even a short period are typically unsalvageable, producing immediate shortages in local markets that translate directly into higher supermarket and fresh-market prices. Fodder loss for cattle hits milk production and dairy incomes, which pushes inflationary pressure into dairy and dairy-derived items.

Inflation and food security: short-term shock, medium-term uncertainty

When staple-producing regions suffer simultaneous crop failure, the immediate economic mechanism is straightforward: lower supply with roughly unchanged demand pushes prices up. But the path from paddies under water to a shopper paying more for rice and vegetables is mediated by three channels:

-

Local mandis and wholesale shocks. As flood-damaged crops hit market supply, mandis in and around Punjab will see fewer arrivals. Because traders often speculate and hedge on expected arrivals during harvest weeks, sudden shortages can trigger sharp intra-week price spikes. Reuters and other reporting on this crisis warned that paddy price openings could move significantly from forecasts due to the damage. Reuters

-

Procurement and public distribution. If Punjab supplies less rice for public procurement, the government faces a choice: release buffer stocks, divert procurement from other states (raising transport costs), or accept lower overall supply into the PDS funnel. Moneycontrol and other analysts flagged the risk that the public distribution machinery may have to stretch to meet domestic needs—an action that can stabilise retail prices temporarily but strains government budgets and reserves.

-

Cascading cost inflation. Beyond staples, vegetable shortages—especially onions, tomatoes and local short-season greens—can spike CPI food inflation quickly. Dairy disruptions from fodder losses may result in temporary milk shortages or increased farm-gate milk prices. Input costs may rise if seed and fertiliser markets react to increased demand from re-sowing attempts. These linkages feed the broader consumer price index and the cost of living for ordinary households. Expert commentary in the days after the floods warned of likely short-term price rises in paddy-related goods and potential knock-on effects in food inflation if the damage persists into the next sowing cycle.

A crucial caveat: price effects differ by geography and duration. Urban consumers in distant states will see slow-moving or more muted impacts because supply channels and inter-state stocks cushion shock; rural households immediately adjacent to flooded areas face steeper local price increases and income loss simultaneously—an especially painful combination.

How long until recovery? Why "weeks" may become "seasons"

Agricultural recovery is not simply about draining fields and planting again. The timeline for normalcy depends on multiple factors:

-

Crop stage at flooding: If paddy was at the grain-filling stage, the yield is irretrievably lost. If seedlings were washed away early in the growing season, farmers might replant—but delayed planting often reduces yields. Where basmati or other premium varieties were damaged at a late stage, lost price premiums and market contracts may have longer-term effects.

-

Soil and infrastructure damage: Floodwaters can deposit silt, sand and contaminants that reduce soil fertility and complicate sowing. Rehabilitating bunds and drainage, restoring pumps and electricity, and clearing blocked rural roads all take time and money.

-

Seed, fertiliser and credit access: Farmers who lost crop and inputs will need seeds, fertiliser and working capital to replant. If banks and cooperatives don’t provide emergency credit quickly, replanting windows may be missed. The adequacy and timeliness of compensation or disaster finance therefore determine whether recovery happens within a season or stretches into the next.

-

Livestock recovery: Lost cattle, disrupted milk collection centres, and destroyed fodder stocks mean dairy production can take months to normalise, affecting incomes and milk availability.

Given these elements, the consensus among agri-economists and field reports is sobering: full recovery for affected farming communities is likely to take at least several months and possibly multiple cropping seasons—especially if the finance and inputs needed to replant are slow to arrive. The policy decisions in the weeks after the floods—rapid cash compensation, expedited seed and fertiliser distribution, quick repair to irrigation and roads—will be decisive in shortening that timeline. Otherwise, what could have been a single-season shock risks cascading into longer-term income stress and migration pressures.

Infrastructure and logistics: how floods amplify supply-chain friction

Flooding is not only a primary agricultural shock: it cripples the infrastructure that moves goods. Blocked rural roads stop trucks carrying fresh produce to mandis; damaged storage yards and warehouses cause rot; local electricity outages affect cold storage for perishables. Even where central grain depots are intact, the last-mile transport breakdowns are costly.

Several market participants reported that agricultural procurement and mandi activity slowed due to connectivity problems and uncertainty about crop quality. That disruption raises transaction costs: traders may demand higher margins for risk, leading to pass-through price increases for consumers. In the longer term, damaged rural roads and bridges must be repaired—an infrastructure bill that states and the Centre will need to prioritise if they want to prevent recurrent supply disruptions during the next harvest.

The human toll: lost income, displacement and food access

Beyond macro numbers, the floods are a story of households forced to choose between basic needs. Farmers who survive distress are not automatic winners: crop loss often coincides with debt repayment schedules, fertilizer loans and seasonal credit obligations. Many smallholders operate on razor-thin margins and rely on seasonal harvests to fund the next sowing; a lost harvest upends that cycle and pushes families to borrow or sell assets at distress prices.

Food access is also threatened at the household level. Families who sell part of their production to buy essential goods now face both lower household income and higher local prices—an inflation-income squeeze. For day labourers and agricultural workers who rely on local harvest work for cash wages, the loss of a harvest cuts immediate job opportunities and wages. Relief camps supply food and water for immediate survival, but long-term food security depends on restoring income and local markets. AP News

Government finance and compensation: debate over adequacy

From the earliest surveys, state leaders in Punjab have argued that the existing compensation norms per acre are inadequate relative to actual farmer losses. At the same time, they have requested the release of pending central funds—RDF and MDF sums they say would help immediate relief and later rebuilding. The political debate is alive: calls for higher per-acre compensation, debt relief, housing reconstruction, livestock aid and a broader relief package have come from across the political spectrum.

But bureaucratic processes take time. Compensation calculations, verification of damage, release of funds—these require on-ground assessment and paperwork. Farmers and local leaders fear that by the time funds arrive, planting decisions will already be made and opportunities lost. That gap—between the need for immediate reconstruction finance and the time-bound realities of agriculture—is the single most critical policy problem. If compensation and seed/fertiliser support are expedited, a large fraction of farmers might replant within the season and limit permanent loss. If not, the damage becomes structural.

The role of insurance and risk transfer—where the gaps are

Crop insurance schemes exist in India, but coverage, timeliness of claims and awareness vary widely. Where farmers are uninsured or underinsured, the burden of loss falls fully on household balance sheets. Where insurance claims are filed, delays and verification processes often slow payouts. The floods have again exposed the limits of current social protection for farmers: insurance must be paired with faster claims adjudication and easier access for smallholders if it is to be an effective resilience tool. Government and insurer coordination will therefore matter for how quickly rural incomes can be stabilised. (Media coverage indicates the need to streamline these systems, but also shows that immediate field-level relief has been coming mainly from civil society and community channels.)

Community resilience: Sikh institutions, diaspora aid and volunteer networks

One remarkable aspect of this disaster has been the scale and speed of community-driven relief—led in large part by Sikh institutions (gurudwaras, Khalsa Aid, local trusts), local teams and diaspora networks. Punjab’s social infrastructure includes deeply rooted patterns of voluntary service (seva), rapid mobilization through religious institutions and cross-border diaspora remittances, all of which translated quickly into ration kits, water trucks, medical camps and temporary shelters. Sikh charities and local volunteers often reached hamlets earlier than formal agencies, providing immediate relief that governments later supplement.

Diaspora contributions included both cash and in-kind support; social media and artist platforms were used to signal needs and coordinate volunteers and supply points. That said, reliance on charity and voluntarism is no substitute for a robust, well-funded official disaster-response and reconstruction plan—especially when the magnitude of damage covers hundreds of thousands of acres across dozens of administrative blocks.

Celebrity action: adoption of villages and public attention

There is no question that celebrity involvement—Diljit Dosanjh adopting villages, Ammy Virk pledging to rebuild 200 homes, and other artists publicising relief drives—brought both tangible resources and media attention. These interventions had two important effects: a practical one (food, medicines, short-term shelter and rehabilitation work reached victims quickly) and a political one (increased public scrutiny on the scale of loss and pressure on governments to act). Yet celebrity action is inherently uneven and cannot scale to replace systemic compensation, rebuilding of rural infrastructure, and long-term livelihood support. The efficient path to recovery still runs through coordinated government finance, state and central procurement policies, and targeted programmes for farm rehabilitation.

What should be done now? Immediate and medium-term policy priorities

Based on the lessons of past flood episodes and the current unfolding reality, a recovery strategy for Punjab and the wider northern flood-hit belt should include the following, implemented together and quickly:

-

Immediate emergency finance and rapid cash transfers. Administrative verification procedures must be simplified so that affected households and landowners receive emergency cash based on satellite imagery, sample verification and self-declarations—fast money helps people replant, buy seed and stabilise consumption.

-

Seed, fertiliser and equipment distribution. Mobilise state and central stocks of seeds and fertiliser for immediate dispatch to flooded blocks on priority routes; waive or defer fees where necessary.

-

Rapid assessment and accelerated insurance claims. Fast-tracked damage assessments—using drone and satellite imagery—should feed an expedited claims process for insured farmers; parallel, simplified compensation for the uninsured.

-

Repair of irrigation, roads and cold-chain. Clearing and repairing rural roads, replacing damaged pumps and restoring cold storage will allow markets to function again and reduce post-harvest losses.

-

Protect PDS and buffer stock management. The Centre should evaluate procurement needs and be ready to release buffer stocks or fund additional procurement from alternative states to ensure PDS continuity without sudden price increases.

-

Livestock support and fodder supply. Provide fodder and veterinary kits immediately to prevent dairy collapses and stabilise milk incomes.

-

Longer-term climate adaptation planning. Reassess embankment design, drainage, floodplain zoning and upstream watershed management; strengthen early-warning systems and community flood preparedness.

Implementation will require immediate fiscal transfers and cross-ministry coordination. The political and administrative will to get money and materials to villages in days—not months—will be decisive. Learnings from past disasters show that where funds and inputs are delayed, temporary calamity morphs into chronic rural distress.

How long will recovery cost and take?

Quantifying the total economic cost is a complex exercise that includes direct crop loss, livestock damage, rebuilding of homes and infrastructure, market disruption and longer-run impacts on wages and migration. Early estimates from district officials and agricultural ministries generally point to large losses running into multiple thousands of crores (tens of billions INR). Punjab’s leaders have requested immediate release of long-pending funds and higher per-acre compensation; their estimates and pleas underline the scale of reconstruction financing needed.

Realistically, full economic normalisation for affected districts will take several months to multiple cropping seasons: fields must be cleared and rehabilitated, farmers need to replace seed and fertiliser, road and market logistics must be restored, and dairy systems need fodder and veterinary support. For households with large debt burdens, financial recovery may take longer still unless debt relief or bridge financing is provided.

What it means for the common person: food, prices and livelihoods

For urban consumers, food price increases are the most tangible immediate effect—if paddy and key vegetables are scarcer, wholesale and retail prices are likely to nudge upward. For rural households in the affected districts, the double hit of lost harvest and higher local prices is more painful: less income and greater expenditure on essentials.

For labourers and small traders who depend on a healthy harvest cycle, weeks of income could vanish. Women and children, often disproportionately affected in disasters, may experience worse food security and interrupted schooling if evacuation and recovery are prolonged. The psychological and social cost—migration to cities, strained social networks, disrupted marriages and schooling—are secondary but long-lasting consequences.

The narratives that matter: blame, solidarity and lessons

A crisis as widespread as this one invites three kinds of public narrative: attribution (who or what caused the failure), solidarity (who helped and how), and learning (what must change next time). The attribution conversation has touched climate-change risk—scientists and commentators have warned that hotter seas and a warmer atmosphere make heavy downpours more likely—and on governance choices like embankment maintenance, land-use planning and urban drainage. Solidarity has been shown in volunteers, Sikh organisations and celebrity interventions. The learning must be structural: investing in resilience now will reduce the astronomical cost of repeated reconstruction in the future.

Closing: urgency, empathy and a path forward

At the time of writing, Punjab’s flooded fields read like a ledger of what a future without climate-resilient systems might cost: lost crops, ruined livelihoods, and the fracturing of trust when official support lags. Yet the same coverage shows the best of local social capital: Sikh volunteers and diaspora, gurudwaras, neighbourhood teams, and artists who converted their stardom into actionable help.

The practical lesson for policymakers is straightforward but demanding: act fast, act big, and think long-term. Fast money and seed distribution can shorten the harvest-to-replant window. Bigger compensation and debt support will stabilise families. A long-term push to repair and redesign flood defences, drainage and cropping calendars for a warming climate will make future seasons less traumatic.

For the families in the villages adopted by performers and supported by volunteers, there is relief and hope. For the wider country, the floods are a test: whether short-term charity is converted into a nation-scale rebuilding that reduces future risk and ensures that a single bad monsoon does not become a generation-long penury.

What's Your Reaction?